Comics' magna opera: Part One - the quasi-masterpieces

In comics, we speak of "runs" by creators that imprint themselves indelibly on the minds of readers. These are usually linked to a certain writer, or perhaps a writer/artist team, but rarely specifically to an artist. These are comics that, I would argue, everyone agrees upon as masterpieces - that's not to say that they are universally loved. We can agree that "Hamlet" is Shakespeare's masterpiece even if we don't like the play, right? What I want to examine in this post is the masterpieces of modern comics, and in a somewhat more general context, what happens after you write one?

The idea of a magnum opus in comics is a relatively new one, I would think. Bear in mind I'm not a comics historian, so I could be horribly wrong-headed, but I don't think so. In the early years of comics, they were completely disposable entertainment, and often creators didn't even get credit for the work they were doing (Bill Finger, anyone?). This practice continued in mainstream comics for years, and even after the situation was rectified, the creators didn't own their work and weren't compensated too well for it. The idea that the creators would conscientiously sit down to write a masterpiece (I know, no one decides that, but again, bear with me) wasn't part of the program in comics. We can speak all we want about Lee and Kirby's remarkable run on Fantastic Four, but does it constitute a masterpiece? Maybe. But reading those issues, although they are important from a comics point of view, it doesn't feel like Lee and Kirby were trying to form a coherent whole with their work. They were just cranking out an issue a month, and over the years, it became, perhaps, their masterpiece.

So, in comics, what does constitute a masterpiece? Well, that's a good question. I have made it no secret that I am far more likely to pay attention to the writing side of comics rather than the artistic, simply because I can break down the written part better than the art on any given book. So when I consider masterpieces in comics, my definition will tend toward something that is written. In my mind, a masterpiece has to be a highly regarded work by a writer (or, again, a writer/artist team) on a book for a given length of time, which means that it should be longer than six months or so. Of the masterpieces I am thinking about, only one (Watchmen, which I'll consider in the next installment) is twelve issues. The rest span several years, which gives them a strength and staying power that shorter runs lack. I also don't know if I can consider a graphic novel - one and done - as a masterpiece. We'll see as we go through this. Maybe one will pop up. A magnum opus should also do one of two things: change the way we look at comics OR reveal something about the creator. With this in mind, I want to look at comics that might not be the absolute best work by the writer (Planetary is not Ellis' masterpiece, for instance, although that has as much as it not being finished as other reasons), but the work that best shows us his view of the world and personality (for this reason, Ellis' entry here is Transmetropolitan). You can argue with my definitions, but of all the masterpieces I can think of in realms other than comics, it seems like it's also very often the artist's most personal work. Again, I could be wrong.

So, when do comic book creators shift from being wage slaves to auteurs and we can begin to consider whether what they're working on is a masterpiece? Ah, a fine question. And the easy answer is: the 1970s.

Consider Bernie Wrightson. Or Steve Gerber. Or Jack Kirby. I haven't read the early Swamp Thing issues or Howard the Duck or the Fourth World saga, but it seems that many people consider them seminal works in the creator-driven comics world we now inhabit. Perhaps we should call them proto-masterpieces. But the 1970s saw a shift toward this idea of comics as a long-running novel or mythic epic, and writers and artists began treating them more like stories that fit together in a more cohesive fashion. Granted, Lee and his Marvel ilk had done this in the 1960s, but not to the extent that later writers did. So in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we had the early masterpieces. These were created within the framework of comics' corporate culture, but are still able to transcend those constraints.

So what are a few of the epics? In this installment (this is a long post, so I thought I'd split it up) I want to look at what I would call quasi-masterpieces. They are works that we associate most readily with a certain creator, but they are still corporate characters, and therefore the creators could not do what they may have wanted completely, and of course the characters continue after the creator is done with them. Therefore, as great as the runs of these titles were, I don't know if they can be considered true magna opera - there's just too much editorial control. This can be a good thing (as our first case shows), but it can also curb the infusion of the creators' personality into the work and also make sure that the character cannot follow a true realistic arc, simply because he or she can't die. They are, however, the best these creators could do under the circumstances.

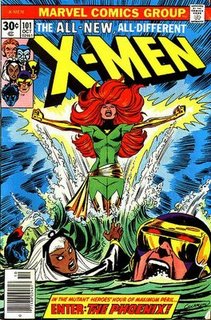

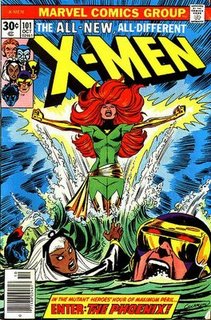

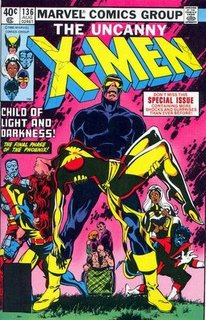

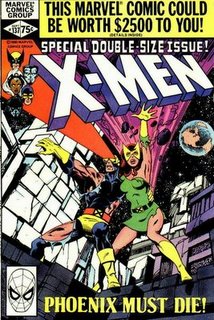

Chris Claremont and John Byrne's masterpiece: Uncanny X-Men #100-138, the Phoenix cycle, August 1976-October 1980. Well, Byrne came on a bit late (issue #108), so I guess part of this could be called Cockrum's masterpiece as well, but this is really Claremont's and Byrne's baby. Basically, Claremont wanted to use his persecuted mutants to tell the story of Jesus. Not too ambitious, is it? At the end of issue #100, Jean Grey uses her telekinesis to land the space shuttle that the X-Men are using to fly back to earth after their adventure in space. She is bombarded with radiation from a solar flare. The issue ends with everyone thinking she's going to die, and at the beginning of issue #101, the shuttle crashes into Jamaica Bay and everyone thinks Jean is dead. She rises from the water as Phoenix, however, and Claremont's epic begins. After Jean recovers from the trauma of her experience, the first fight she gets into is with Firelord, and then she saves the universe. Not too shabby.

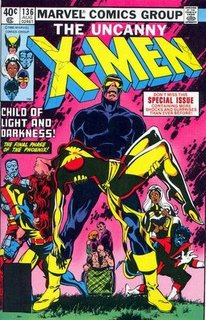

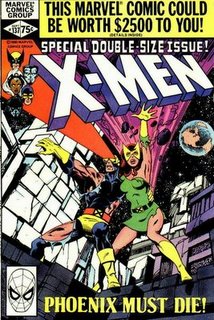

Chris Claremont and John Byrne's masterpiece: Uncanny X-Men #100-138, the Phoenix cycle, August 1976-October 1980. Well, Byrne came on a bit late (issue #108), so I guess part of this could be called Cockrum's masterpiece as well, but this is really Claremont's and Byrne's baby. Basically, Claremont wanted to use his persecuted mutants to tell the story of Jesus. Not too ambitious, is it? At the end of issue #100, Jean Grey uses her telekinesis to land the space shuttle that the X-Men are using to fly back to earth after their adventure in space. She is bombarded with radiation from a solar flare. The issue ends with everyone thinking she's going to die, and at the beginning of issue #101, the shuttle crashes into Jamaica Bay and everyone thinks Jean is dead. She rises from the water as Phoenix, however, and Claremont's epic begins. After Jean recovers from the trauma of her experience, the first fight she gets into is with Firelord, and then she saves the universe. Not too shabby. However, this presented a problem for Claremont: when you have a mutant who can, quite literally, stitch the universe back together, how do you come up with threats that she can't defeat? Claremont and Byrne came up with some ideas - mind control and when she thought the X-Men were dead so they could have adventures without her - but eventually they were going to have to address the fact that she was probably the most powerful mutant on the planet. This came with the Dark Phoenix part of the cycle, which, if we keep the Jesus metaphor going (and why not?) is when she descends into hell. No, she doesn't get crucified, but her mental torment and fall from grace, leading to the crime of killing millions of sentient beings, is hellish enough. Claremont and Byrne had worked themselves into a corner with this one, and despite the controversy over what should happen to Jean Grey, Phoenix's sacrifice in issue #137 is the only way, really, that the story could have ended - not because of editorial mandate and the fact that Marvel couldn't allow a mass murderer to continue as a hero on a best-selling book, but because thematically, it was what Claremont and Byrne had been working toward, no matter how much they try to deny it. Jean sacrifices herself to save the world, just as she was ready to sacrifice herself in issue #108 to save the world. In that instance, she was strong enough to do the heroic thing, but by issue #137, she isn't. The very nature of the Phoenix as well demands sacrifice. Jean "died" in issue #101 and was resurrected by the Phoenix. She dies again in issue #137.

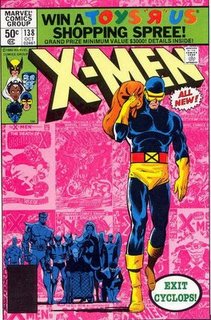

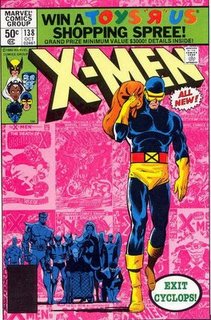

However, this presented a problem for Claremont: when you have a mutant who can, quite literally, stitch the universe back together, how do you come up with threats that she can't defeat? Claremont and Byrne came up with some ideas - mind control and when she thought the X-Men were dead so they could have adventures without her - but eventually they were going to have to address the fact that she was probably the most powerful mutant on the planet. This came with the Dark Phoenix part of the cycle, which, if we keep the Jesus metaphor going (and why not?) is when she descends into hell. No, she doesn't get crucified, but her mental torment and fall from grace, leading to the crime of killing millions of sentient beings, is hellish enough. Claremont and Byrne had worked themselves into a corner with this one, and despite the controversy over what should happen to Jean Grey, Phoenix's sacrifice in issue #137 is the only way, really, that the story could have ended - not because of editorial mandate and the fact that Marvel couldn't allow a mass murderer to continue as a hero on a best-selling book, but because thematically, it was what Claremont and Byrne had been working toward, no matter how much they try to deny it. Jean sacrifices herself to save the world, just as she was ready to sacrifice herself in issue #108 to save the world. In that instance, she was strong enough to do the heroic thing, but by issue #137, she isn't. The very nature of the Phoenix as well demands sacrifice. Jean "died" in issue #101 and was resurrected by the Phoenix. She dies again in issue #137. It's logical, and adds power to the Jesus metaphor that Claremont and Byrne deliberately set up. Issue #138 adds a strong coda, as Cyclops, a founding member of the team, leaves. The X-Men have been severed from their past, and this adds poignancy to the Phoenix saga as well. These two people, who grew up together and experienced the highs and the lows of being a mutant superhero, have "grown up," so to speak - Jean because she was able to make the ultimate sacrifice, and Scott because he was able to leave his "family."

It's logical, and adds power to the Jesus metaphor that Claremont and Byrne deliberately set up. Issue #138 adds a strong coda, as Cyclops, a founding member of the team, leaves. The X-Men have been severed from their past, and this adds poignancy to the Phoenix saga as well. These two people, who grew up together and experienced the highs and the lows of being a mutant superhero, have "grown up," so to speak - Jean because she was able to make the ultimate sacrifice, and Scott because he was able to leave his "family."

So what happened next? Claremont continued to write the book for another eleven years, and despite some very strong work (even after Paul Smith left), he was never able to recapture the magic. I would argue that Uncanny X-Men #94-280 form one of the most satisfying pieces of literature you'd ever want to read, but I may be biased. The problem with Claremont is not that Byrne left the book, but that he just isn't all that good a writer. That's not to say he doesn't have his strengths - plotting and characterization (but not dialogue) among them - but his mythology that he created in those first 40 issues of the X-Men eventually took over and he became a self-perpetuating mutant mogul, concerned with the franchise more than the stories. Again, that's not to say they were bad comics - and Claremont has certainly done more with the X-Men as a mythology than any writer since, with the possible exception of Morrison. But when you've made a cornerstone of the Marvel Universe into an omnipotent being capable of re-imagining reality and then you kill her, you really don't have a lot of places to go but down. Claremont's limitations as a writer (his reliance on catchphrases, for instance, which I know is partly because of the serial nature of comics, but doesn't forgive it) made his post-Phoenix work somewhat hit-and-miss. Even in issues that I think are highpoints of his later X-Men (the Jim Lee Psylocke trilogy comes to mind), the actual words on the page are occasionally painful to read. Byrne, on the other hand, just went insane.

I would argue that Uncanny X-Men #94-280 form one of the most satisfying pieces of literature you'd ever want to read, but I may be biased. The problem with Claremont is not that Byrne left the book, but that he just isn't all that good a writer. That's not to say he doesn't have his strengths - plotting and characterization (but not dialogue) among them - but his mythology that he created in those first 40 issues of the X-Men eventually took over and he became a self-perpetuating mutant mogul, concerned with the franchise more than the stories. Again, that's not to say they were bad comics - and Claremont has certainly done more with the X-Men as a mythology than any writer since, with the possible exception of Morrison. But when you've made a cornerstone of the Marvel Universe into an omnipotent being capable of re-imagining reality and then you kill her, you really don't have a lot of places to go but down. Claremont's limitations as a writer (his reliance on catchphrases, for instance, which I know is partly because of the serial nature of comics, but doesn't forgive it) made his post-Phoenix work somewhat hit-and-miss. Even in issues that I think are highpoints of his later X-Men (the Jim Lee Psylocke trilogy comes to mind), the actual words on the page are occasionally painful to read. Byrne, on the other hand, just went insane.

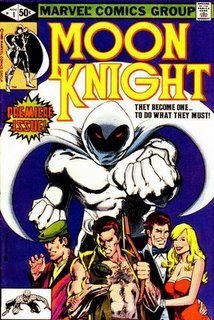

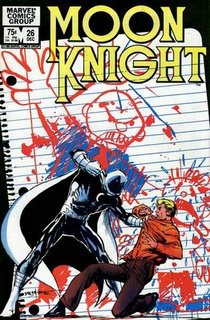

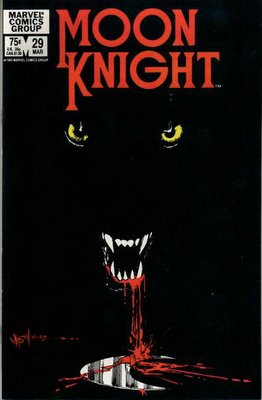

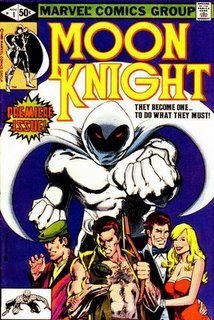

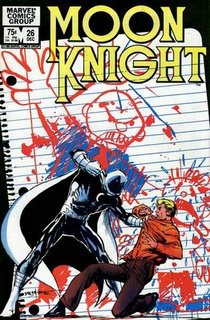

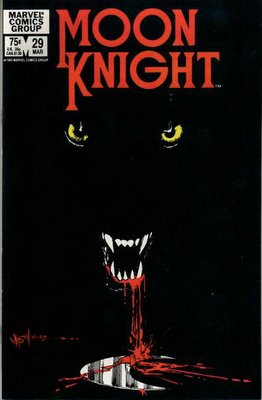

Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz's masterpiece: Moon Knight #1-30, November 1980-April 1983. Those people who were mystified by the fan reaction (including mine) to the latest relaunch of Moon Knight have either never read these issues or read them with a cold, black heart. I'm actually a little wary about calling this a masterpiece - certainly I hold them in high regard, but I'm not sure if they hold up in terms of epic storytelling. It's certainly not Sienkiewicz's best work - he was still aping Neal Adams at the beginning of the run, and only slowly evolved into the master he was at the end of the run, but I'm not sure what his masterpiece would be, which is why it's hard to focus on artists for this post. Sienkiewicz's magnum opus could certainly be something shorter than the parameters I've set out - Elektra: Assassin or Stray Toasters or even Big Numbers, of which only two issues saw print. This is certainly the longest he's ever spent on a title, however, and the art is gripping and fun to watch as he gains confidence.

Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz's masterpiece: Moon Knight #1-30, November 1980-April 1983. Those people who were mystified by the fan reaction (including mine) to the latest relaunch of Moon Knight have either never read these issues or read them with a cold, black heart. I'm actually a little wary about calling this a masterpiece - certainly I hold them in high regard, but I'm not sure if they hold up in terms of epic storytelling. It's certainly not Sienkiewicz's best work - he was still aping Neal Adams at the beginning of the run, and only slowly evolved into the master he was at the end of the run, but I'm not sure what his masterpiece would be, which is why it's hard to focus on artists for this post. Sienkiewicz's magnum opus could certainly be something shorter than the parameters I've set out - Elektra: Assassin or Stray Toasters or even Big Numbers, of which only two issues saw print. This is certainly the longest he's ever spent on a title, however, and the art is gripping and fun to watch as he gains confidence.

As for Moench, he's a guy who's been around forever but never gets quite the credit he deserves. Again, I'm not sure if this counts as his masterpiece - whether he even has one is another question. This and his mid-1990s run on Batman are probably his two best works, but with Batman, although it is a fine piece of comics literature, he was a mite too didactic, and this affected the work a bit. That's not to say comics can't teach us something, but too often in Batman, Moench made that his whole point. He created Moon Knight in 1976 and was given this opportunity to write the ongoing series, and that's why I count this as his grand work - it's a personal project to him, and he rose to the occasion.

The most fascinating thing about Moon Knight, of course, is his multiple personalities. Writers always hint around the duality of superheroes and their secret identities, but Moench took the next logical step and made Marc Spector a man with many personalities, of which Moon Knight was just one. This allowed him to shunt various aspects of his personality into these personae - Spector was the brutish lout who could kill without compunction; Grant was the urbane millionaire who charmed the ladies; Lockley was the sleuth with all sorts of street connections; Moon Knight was the avenger. Moench is best when showing how these personae conflict with each other - Marlene is constantly bugging Steven Grant to step up, but he often must remain in the background. The persona of a globe-trotting mercenary beholden to an Egyptian god allowed Moench to tell adventure stories, such as when Spector fights Bushman, but the persona of a street-smart cabbie allowed him to tell gritty, tough stories set deep in the darkness of New York, too, such as the Stained Glass Scarlett story and the domestic abuse story, "Hit It," in issue #26. Moench, like Sienkiewicz, got better as the series went on, as he began to bring in more and more of his own thoughts and theories about the world - I've mentioned before that Moench loves paranoia and mysterious government agencies running things, and these begin to seep in a bit toward the end of this run, especially in issues #29-30, when Jack Russell shows up. It didn't take over the stories (like it did in the two Moon Knight mini-series he wrote in the late 1990s), but it did add an edge to the title that had been lacking in the beginning.

It didn't take over the stories (like it did in the two Moon Knight mini-series he wrote in the late 1990s), but it did add an edge to the title that had been lacking in the beginning.

It's a tough call on this, but I'm going to stick with it not because the book was the highest quality (it's very good, don't get me wrong), but because of its somewhat revolutionary nature. It was one of the first books to be sold in specialty stores exclusively, and the fact that kids couldn't get it on the news stands meant that Moench and Sienkiewicz could afford to be a bit more "adult" with the themes and ideas presented. It also signaled the rise of a major talent in comics and gave us a very interesting character who probably can never be a superstar in the Marvel Universe but could easily be a vehicle for some great stories. Finally, the personal nature of these issues make this more than just a standard "urban warrior" kind of thing. Close call, but I would argue it's a masterpiece.

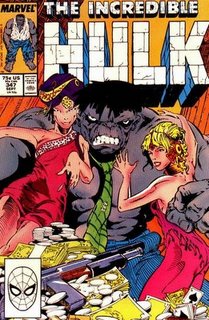

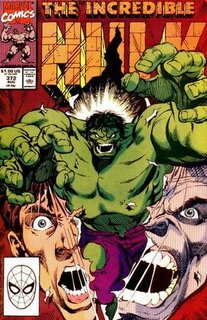

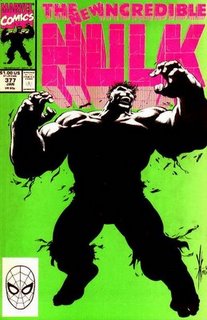

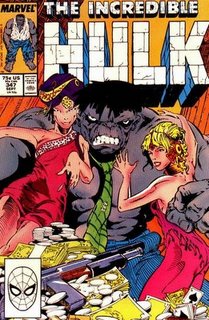

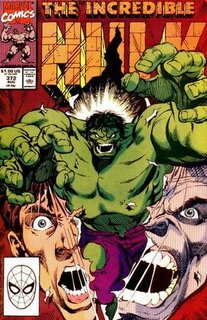

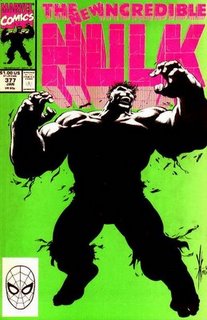

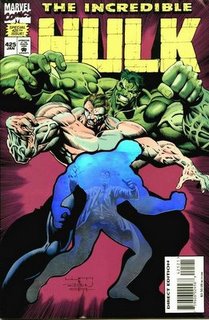

Peter David's masterpiece: The Incredible Hulk, issues #347-425, September 1988-January 1995. I may get some argument from this one, but a few things make this a masterpiece. First, David took an essentially one-note character and made him one of the most complex in the Marvel Universe. Second, he kept re-inventing the Hulk, all the while adding to the whole story that he was creating, which is an impressive achievement. This is not just the arc of Bruce Banner/Hulk's life, it's a radical change every so often, while still keeping the arc of his life running smoothly. I doubt if anyone would have the onions to do this sort of thing with a long-running character like the Hulk, but let's face it - he wasn't much when David took him over. First, David had to clear the decks, and he did that prior to #347 (he started writing the book around issue #332, but that first year or so was only so-so, as he wiped the slate clean). In issue #347, he brings us the gray, intelligent Hulk - Joe Fixit, a Las Vegas mob enforcer. It's a bold move, and one that leads, ultimately, to Rick Jones' marriage to Marlo (Hulk's girlfriend for a time). However, David is not satisfied with simply changing the Hulk completely.

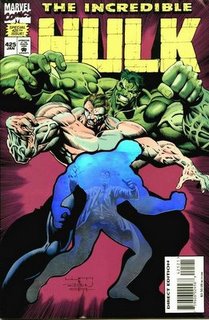

Peter David's masterpiece: The Incredible Hulk, issues #347-425, September 1988-January 1995. I may get some argument from this one, but a few things make this a masterpiece. First, David took an essentially one-note character and made him one of the most complex in the Marvel Universe. Second, he kept re-inventing the Hulk, all the while adding to the whole story that he was creating, which is an impressive achievement. This is not just the arc of Bruce Banner/Hulk's life, it's a radical change every so often, while still keeping the arc of his life running smoothly. I doubt if anyone would have the onions to do this sort of thing with a long-running character like the Hulk, but let's face it - he wasn't much when David took him over. First, David had to clear the decks, and he did that prior to #347 (he started writing the book around issue #332, but that first year or so was only so-so, as he wiped the slate clean). In issue #347, he brings us the gray, intelligent Hulk - Joe Fixit, a Las Vegas mob enforcer. It's a bold move, and one that leads, ultimately, to Rick Jones' marriage to Marlo (Hulk's girlfriend for a time). However, David is not satisfied with simply changing the Hulk completely. He understands that this character is essentially goofy - in the cynical 1980s and 1990s, we just can't accept that a gamma bomb would be able to change a man's physical nature so radically, so David begins to build a foundation of how and why the Hulk is this way. He examines the Hulk's multiple personalities, and even integrates the coloring fiasco that changed the Hulk from gray (in his first appearance) to green (in his subsequent appearances). These problems culminate in several blockbuster issues, including #372 and #377, when we get a fully integrated green Hulk who is intelligent and even urbane. David never stops trying to get to the bottom of who the Hulk actually is - Bruce Banner disappears for long stretches during this run, as David points us to the conclusion that "Banner" is just a façade and the intelligent green Hulk is the true personality. Just when we accept that, David again pulls the rug out from under us and makes us once again question what the Hulk actually is. Finally, in issue #425, another integration develops, and we are again thrown into confusion, as Banner is the raging maniac while the Hulk remains lucid.

He understands that this character is essentially goofy - in the cynical 1980s and 1990s, we just can't accept that a gamma bomb would be able to change a man's physical nature so radically, so David begins to build a foundation of how and why the Hulk is this way. He examines the Hulk's multiple personalities, and even integrates the coloring fiasco that changed the Hulk from gray (in his first appearance) to green (in his subsequent appearances). These problems culminate in several blockbuster issues, including #372 and #377, when we get a fully integrated green Hulk who is intelligent and even urbane. David never stops trying to get to the bottom of who the Hulk actually is - Bruce Banner disappears for long stretches during this run, as David points us to the conclusion that "Banner" is just a façade and the intelligent green Hulk is the true personality. Just when we accept that, David again pulls the rug out from under us and makes us once again question what the Hulk actually is. Finally, in issue #425, another integration develops, and we are again thrown into confusion, as Banner is the raging maniac while the Hulk remains lucid.

David wrote the book for another forty (!) issues, and he probably would have kept on if policy at Marvel hadn't pissed him off, but although the issues after #425 are decent, he had lost a bit of the direction that he had managed to keep for the previous 75 issues or so. The art became sloppy until Adam Kubert came on board late in the run, even though the artists (including Liam Sharp, Mike Deodato, and Angel Medina) have done decent work on other books. Throughout his run on the Hulk, David had a succession of good artists at the top of their game - Jeff Purves, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank - who helped bring his vision to life. David's work, it seemed, became sloppier when the art did, and the succession of crossovers Marvel was indulging in during the mid-1990s didn't help.

David wrote the book for another forty (!) issues, and he probably would have kept on if policy at Marvel hadn't pissed him off, but although the issues after #425 are decent, he had lost a bit of the direction that he had managed to keep for the previous 75 issues or so. The art became sloppy until Adam Kubert came on board late in the run, even though the artists (including Liam Sharp, Mike Deodato, and Angel Medina) have done decent work on other books. Throughout his run on the Hulk, David had a succession of good artists at the top of their game - Jeff Purves, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank - who helped bring his vision to life. David's work, it seemed, became sloppier when the art did, and the succession of crossovers Marvel was indulging in during the mid-1990s didn't help.

What was next for David? He is principally known for his work on the Incredible Hulk, unless people know him for his Star Trek comics. He wrote Aquaman and X-Factor during the time he was writing the Hulk, and since his work on that ended, he has done a lot of other stuff. Right now he's working on Fallen Angel, which might be a masterpiece when it's all said and done, plus various other stuff. With the exception of Fallen Angel, however, which is only 24 issues in, he hasn't done anything that has approached not only his longevity on the Hulk but its sheer inventiveness. He still has a lot of comic book work left in him, though.

What was next for David? He is principally known for his work on the Incredible Hulk, unless people know him for his Star Trek comics. He wrote Aquaman and X-Factor during the time he was writing the Hulk, and since his work on that ended, he has done a lot of other stuff. Right now he's working on Fallen Angel, which might be a masterpiece when it's all said and done, plus various other stuff. With the exception of Fallen Angel, however, which is only 24 issues in, he hasn't done anything that has approached not only his longevity on the Hulk but its sheer inventiveness. He still has a lot of comic book work left in him, though.

As far as quasi-masterpieces, these three are good examples. As I have said many times, my knowledge of comics prior to 1988 is somewhat limited (many people would say my knowledge since 1988 is limited, too), so I know I'm missing several. I would count Walt Simonson on the Mighty Thor (#337-382, roughly), but I only own up to issue #355 and don't want to consider it without having read it. Does Byrne's Fantastic Four count? Didn't Gruenwald write a ton of Captain America comics, and aren't they considered brilliant? Is Michelinie's run on Iron Man a masterpiece? What about Wolfman and Perez on Teen Titans? I'm just wondering.

Anyway, thoughts on this are welcome, as usual. It's very interesting to consider when creators hit their peak and what they do after it.

Next time: the rise of the auteurs!

The idea of a magnum opus in comics is a relatively new one, I would think. Bear in mind I'm not a comics historian, so I could be horribly wrong-headed, but I don't think so. In the early years of comics, they were completely disposable entertainment, and often creators didn't even get credit for the work they were doing (Bill Finger, anyone?). This practice continued in mainstream comics for years, and even after the situation was rectified, the creators didn't own their work and weren't compensated too well for it. The idea that the creators would conscientiously sit down to write a masterpiece (I know, no one decides that, but again, bear with me) wasn't part of the program in comics. We can speak all we want about Lee and Kirby's remarkable run on Fantastic Four, but does it constitute a masterpiece? Maybe. But reading those issues, although they are important from a comics point of view, it doesn't feel like Lee and Kirby were trying to form a coherent whole with their work. They were just cranking out an issue a month, and over the years, it became, perhaps, their masterpiece.

So, in comics, what does constitute a masterpiece? Well, that's a good question. I have made it no secret that I am far more likely to pay attention to the writing side of comics rather than the artistic, simply because I can break down the written part better than the art on any given book. So when I consider masterpieces in comics, my definition will tend toward something that is written. In my mind, a masterpiece has to be a highly regarded work by a writer (or, again, a writer/artist team) on a book for a given length of time, which means that it should be longer than six months or so. Of the masterpieces I am thinking about, only one (Watchmen, which I'll consider in the next installment) is twelve issues. The rest span several years, which gives them a strength and staying power that shorter runs lack. I also don't know if I can consider a graphic novel - one and done - as a masterpiece. We'll see as we go through this. Maybe one will pop up. A magnum opus should also do one of two things: change the way we look at comics OR reveal something about the creator. With this in mind, I want to look at comics that might not be the absolute best work by the writer (Planetary is not Ellis' masterpiece, for instance, although that has as much as it not being finished as other reasons), but the work that best shows us his view of the world and personality (for this reason, Ellis' entry here is Transmetropolitan). You can argue with my definitions, but of all the masterpieces I can think of in realms other than comics, it seems like it's also very often the artist's most personal work. Again, I could be wrong.

So, when do comic book creators shift from being wage slaves to auteurs and we can begin to consider whether what they're working on is a masterpiece? Ah, a fine question. And the easy answer is: the 1970s.

Consider Bernie Wrightson. Or Steve Gerber. Or Jack Kirby. I haven't read the early Swamp Thing issues or Howard the Duck or the Fourth World saga, but it seems that many people consider them seminal works in the creator-driven comics world we now inhabit. Perhaps we should call them proto-masterpieces. But the 1970s saw a shift toward this idea of comics as a long-running novel or mythic epic, and writers and artists began treating them more like stories that fit together in a more cohesive fashion. Granted, Lee and his Marvel ilk had done this in the 1960s, but not to the extent that later writers did. So in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we had the early masterpieces. These were created within the framework of comics' corporate culture, but are still able to transcend those constraints.

So what are a few of the epics? In this installment (this is a long post, so I thought I'd split it up) I want to look at what I would call quasi-masterpieces. They are works that we associate most readily with a certain creator, but they are still corporate characters, and therefore the creators could not do what they may have wanted completely, and of course the characters continue after the creator is done with them. Therefore, as great as the runs of these titles were, I don't know if they can be considered true magna opera - there's just too much editorial control. This can be a good thing (as our first case shows), but it can also curb the infusion of the creators' personality into the work and also make sure that the character cannot follow a true realistic arc, simply because he or she can't die. They are, however, the best these creators could do under the circumstances.

Chris Claremont and John Byrne's masterpiece: Uncanny X-Men #100-138, the Phoenix cycle, August 1976-October 1980. Well, Byrne came on a bit late (issue #108), so I guess part of this could be called Cockrum's masterpiece as well, but this is really Claremont's and Byrne's baby. Basically, Claremont wanted to use his persecuted mutants to tell the story of Jesus. Not too ambitious, is it? At the end of issue #100, Jean Grey uses her telekinesis to land the space shuttle that the X-Men are using to fly back to earth after their adventure in space. She is bombarded with radiation from a solar flare. The issue ends with everyone thinking she's going to die, and at the beginning of issue #101, the shuttle crashes into Jamaica Bay and everyone thinks Jean is dead. She rises from the water as Phoenix, however, and Claremont's epic begins. After Jean recovers from the trauma of her experience, the first fight she gets into is with Firelord, and then she saves the universe. Not too shabby.

Chris Claremont and John Byrne's masterpiece: Uncanny X-Men #100-138, the Phoenix cycle, August 1976-October 1980. Well, Byrne came on a bit late (issue #108), so I guess part of this could be called Cockrum's masterpiece as well, but this is really Claremont's and Byrne's baby. Basically, Claremont wanted to use his persecuted mutants to tell the story of Jesus. Not too ambitious, is it? At the end of issue #100, Jean Grey uses her telekinesis to land the space shuttle that the X-Men are using to fly back to earth after their adventure in space. She is bombarded with radiation from a solar flare. The issue ends with everyone thinking she's going to die, and at the beginning of issue #101, the shuttle crashes into Jamaica Bay and everyone thinks Jean is dead. She rises from the water as Phoenix, however, and Claremont's epic begins. After Jean recovers from the trauma of her experience, the first fight she gets into is with Firelord, and then she saves the universe. Not too shabby. However, this presented a problem for Claremont: when you have a mutant who can, quite literally, stitch the universe back together, how do you come up with threats that she can't defeat? Claremont and Byrne came up with some ideas - mind control and when she thought the X-Men were dead so they could have adventures without her - but eventually they were going to have to address the fact that she was probably the most powerful mutant on the planet. This came with the Dark Phoenix part of the cycle, which, if we keep the Jesus metaphor going (and why not?) is when she descends into hell. No, she doesn't get crucified, but her mental torment and fall from grace, leading to the crime of killing millions of sentient beings, is hellish enough. Claremont and Byrne had worked themselves into a corner with this one, and despite the controversy over what should happen to Jean Grey, Phoenix's sacrifice in issue #137 is the only way, really, that the story could have ended - not because of editorial mandate and the fact that Marvel couldn't allow a mass murderer to continue as a hero on a best-selling book, but because thematically, it was what Claremont and Byrne had been working toward, no matter how much they try to deny it. Jean sacrifices herself to save the world, just as she was ready to sacrifice herself in issue #108 to save the world. In that instance, she was strong enough to do the heroic thing, but by issue #137, she isn't. The very nature of the Phoenix as well demands sacrifice. Jean "died" in issue #101 and was resurrected by the Phoenix. She dies again in issue #137.

However, this presented a problem for Claremont: when you have a mutant who can, quite literally, stitch the universe back together, how do you come up with threats that she can't defeat? Claremont and Byrne came up with some ideas - mind control and when she thought the X-Men were dead so they could have adventures without her - but eventually they were going to have to address the fact that she was probably the most powerful mutant on the planet. This came with the Dark Phoenix part of the cycle, which, if we keep the Jesus metaphor going (and why not?) is when she descends into hell. No, she doesn't get crucified, but her mental torment and fall from grace, leading to the crime of killing millions of sentient beings, is hellish enough. Claremont and Byrne had worked themselves into a corner with this one, and despite the controversy over what should happen to Jean Grey, Phoenix's sacrifice in issue #137 is the only way, really, that the story could have ended - not because of editorial mandate and the fact that Marvel couldn't allow a mass murderer to continue as a hero on a best-selling book, but because thematically, it was what Claremont and Byrne had been working toward, no matter how much they try to deny it. Jean sacrifices herself to save the world, just as she was ready to sacrifice herself in issue #108 to save the world. In that instance, she was strong enough to do the heroic thing, but by issue #137, she isn't. The very nature of the Phoenix as well demands sacrifice. Jean "died" in issue #101 and was resurrected by the Phoenix. She dies again in issue #137. It's logical, and adds power to the Jesus metaphor that Claremont and Byrne deliberately set up. Issue #138 adds a strong coda, as Cyclops, a founding member of the team, leaves. The X-Men have been severed from their past, and this adds poignancy to the Phoenix saga as well. These two people, who grew up together and experienced the highs and the lows of being a mutant superhero, have "grown up," so to speak - Jean because she was able to make the ultimate sacrifice, and Scott because he was able to leave his "family."

It's logical, and adds power to the Jesus metaphor that Claremont and Byrne deliberately set up. Issue #138 adds a strong coda, as Cyclops, a founding member of the team, leaves. The X-Men have been severed from their past, and this adds poignancy to the Phoenix saga as well. These two people, who grew up together and experienced the highs and the lows of being a mutant superhero, have "grown up," so to speak - Jean because she was able to make the ultimate sacrifice, and Scott because he was able to leave his "family."So what happened next? Claremont continued to write the book for another eleven years, and despite some very strong work (even after Paul Smith left), he was never able to recapture the magic.

I would argue that Uncanny X-Men #94-280 form one of the most satisfying pieces of literature you'd ever want to read, but I may be biased. The problem with Claremont is not that Byrne left the book, but that he just isn't all that good a writer. That's not to say he doesn't have his strengths - plotting and characterization (but not dialogue) among them - but his mythology that he created in those first 40 issues of the X-Men eventually took over and he became a self-perpetuating mutant mogul, concerned with the franchise more than the stories. Again, that's not to say they were bad comics - and Claremont has certainly done more with the X-Men as a mythology than any writer since, with the possible exception of Morrison. But when you've made a cornerstone of the Marvel Universe into an omnipotent being capable of re-imagining reality and then you kill her, you really don't have a lot of places to go but down. Claremont's limitations as a writer (his reliance on catchphrases, for instance, which I know is partly because of the serial nature of comics, but doesn't forgive it) made his post-Phoenix work somewhat hit-and-miss. Even in issues that I think are highpoints of his later X-Men (the Jim Lee Psylocke trilogy comes to mind), the actual words on the page are occasionally painful to read. Byrne, on the other hand, just went insane.

I would argue that Uncanny X-Men #94-280 form one of the most satisfying pieces of literature you'd ever want to read, but I may be biased. The problem with Claremont is not that Byrne left the book, but that he just isn't all that good a writer. That's not to say he doesn't have his strengths - plotting and characterization (but not dialogue) among them - but his mythology that he created in those first 40 issues of the X-Men eventually took over and he became a self-perpetuating mutant mogul, concerned with the franchise more than the stories. Again, that's not to say they were bad comics - and Claremont has certainly done more with the X-Men as a mythology than any writer since, with the possible exception of Morrison. But when you've made a cornerstone of the Marvel Universe into an omnipotent being capable of re-imagining reality and then you kill her, you really don't have a lot of places to go but down. Claremont's limitations as a writer (his reliance on catchphrases, for instance, which I know is partly because of the serial nature of comics, but doesn't forgive it) made his post-Phoenix work somewhat hit-and-miss. Even in issues that I think are highpoints of his later X-Men (the Jim Lee Psylocke trilogy comes to mind), the actual words on the page are occasionally painful to read. Byrne, on the other hand, just went insane. Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz's masterpiece: Moon Knight #1-30, November 1980-April 1983. Those people who were mystified by the fan reaction (including mine) to the latest relaunch of Moon Knight have either never read these issues or read them with a cold, black heart. I'm actually a little wary about calling this a masterpiece - certainly I hold them in high regard, but I'm not sure if they hold up in terms of epic storytelling. It's certainly not Sienkiewicz's best work - he was still aping Neal Adams at the beginning of the run, and only slowly evolved into the master he was at the end of the run, but I'm not sure what his masterpiece would be, which is why it's hard to focus on artists for this post. Sienkiewicz's magnum opus could certainly be something shorter than the parameters I've set out - Elektra: Assassin or Stray Toasters or even Big Numbers, of which only two issues saw print. This is certainly the longest he's ever spent on a title, however, and the art is gripping and fun to watch as he gains confidence.

Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz's masterpiece: Moon Knight #1-30, November 1980-April 1983. Those people who were mystified by the fan reaction (including mine) to the latest relaunch of Moon Knight have either never read these issues or read them with a cold, black heart. I'm actually a little wary about calling this a masterpiece - certainly I hold them in high regard, but I'm not sure if they hold up in terms of epic storytelling. It's certainly not Sienkiewicz's best work - he was still aping Neal Adams at the beginning of the run, and only slowly evolved into the master he was at the end of the run, but I'm not sure what his masterpiece would be, which is why it's hard to focus on artists for this post. Sienkiewicz's magnum opus could certainly be something shorter than the parameters I've set out - Elektra: Assassin or Stray Toasters or even Big Numbers, of which only two issues saw print. This is certainly the longest he's ever spent on a title, however, and the art is gripping and fun to watch as he gains confidence.As for Moench, he's a guy who's been around forever but never gets quite the credit he deserves. Again, I'm not sure if this counts as his masterpiece - whether he even has one is another question. This and his mid-1990s run on Batman are probably his two best works, but with Batman, although it is a fine piece of comics literature, he was a mite too didactic, and this affected the work a bit. That's not to say comics can't teach us something, but too often in Batman, Moench made that his whole point. He created Moon Knight in 1976 and was given this opportunity to write the ongoing series, and that's why I count this as his grand work - it's a personal project to him, and he rose to the occasion.

The most fascinating thing about Moon Knight, of course, is his multiple personalities. Writers always hint around the duality of superheroes and their secret identities, but Moench took the next logical step and made Marc Spector a man with many personalities, of which Moon Knight was just one. This allowed him to shunt various aspects of his personality into these personae - Spector was the brutish lout who could kill without compunction; Grant was the urbane millionaire who charmed the ladies; Lockley was the sleuth with all sorts of street connections; Moon Knight was the avenger. Moench is best when showing how these personae conflict with each other - Marlene is constantly bugging Steven Grant to step up, but he often must remain in the background. The persona of a globe-trotting mercenary beholden to an Egyptian god allowed Moench to tell adventure stories, such as when Spector fights Bushman, but the persona of a street-smart cabbie allowed him to tell gritty, tough stories set deep in the darkness of New York, too, such as the Stained Glass Scarlett story and the domestic abuse story, "Hit It," in issue #26. Moench, like Sienkiewicz, got better as the series went on, as he began to bring in more and more of his own thoughts and theories about the world - I've mentioned before that Moench loves paranoia and mysterious government agencies running things, and these begin to seep in a bit toward the end of this run, especially in issues #29-30, when Jack Russell shows up.

It didn't take over the stories (like it did in the two Moon Knight mini-series he wrote in the late 1990s), but it did add an edge to the title that had been lacking in the beginning.

It didn't take over the stories (like it did in the two Moon Knight mini-series he wrote in the late 1990s), but it did add an edge to the title that had been lacking in the beginning.It's a tough call on this, but I'm going to stick with it not because the book was the highest quality (it's very good, don't get me wrong), but because of its somewhat revolutionary nature. It was one of the first books to be sold in specialty stores exclusively, and the fact that kids couldn't get it on the news stands meant that Moench and Sienkiewicz could afford to be a bit more "adult" with the themes and ideas presented. It also signaled the rise of a major talent in comics and gave us a very interesting character who probably can never be a superstar in the Marvel Universe but could easily be a vehicle for some great stories. Finally, the personal nature of these issues make this more than just a standard "urban warrior" kind of thing. Close call, but I would argue it's a masterpiece.

Peter David's masterpiece: The Incredible Hulk, issues #347-425, September 1988-January 1995. I may get some argument from this one, but a few things make this a masterpiece. First, David took an essentially one-note character and made him one of the most complex in the Marvel Universe. Second, he kept re-inventing the Hulk, all the while adding to the whole story that he was creating, which is an impressive achievement. This is not just the arc of Bruce Banner/Hulk's life, it's a radical change every so often, while still keeping the arc of his life running smoothly. I doubt if anyone would have the onions to do this sort of thing with a long-running character like the Hulk, but let's face it - he wasn't much when David took him over. First, David had to clear the decks, and he did that prior to #347 (he started writing the book around issue #332, but that first year or so was only so-so, as he wiped the slate clean). In issue #347, he brings us the gray, intelligent Hulk - Joe Fixit, a Las Vegas mob enforcer. It's a bold move, and one that leads, ultimately, to Rick Jones' marriage to Marlo (Hulk's girlfriend for a time). However, David is not satisfied with simply changing the Hulk completely.

Peter David's masterpiece: The Incredible Hulk, issues #347-425, September 1988-January 1995. I may get some argument from this one, but a few things make this a masterpiece. First, David took an essentially one-note character and made him one of the most complex in the Marvel Universe. Second, he kept re-inventing the Hulk, all the while adding to the whole story that he was creating, which is an impressive achievement. This is not just the arc of Bruce Banner/Hulk's life, it's a radical change every so often, while still keeping the arc of his life running smoothly. I doubt if anyone would have the onions to do this sort of thing with a long-running character like the Hulk, but let's face it - he wasn't much when David took him over. First, David had to clear the decks, and he did that prior to #347 (he started writing the book around issue #332, but that first year or so was only so-so, as he wiped the slate clean). In issue #347, he brings us the gray, intelligent Hulk - Joe Fixit, a Las Vegas mob enforcer. It's a bold move, and one that leads, ultimately, to Rick Jones' marriage to Marlo (Hulk's girlfriend for a time). However, David is not satisfied with simply changing the Hulk completely. He understands that this character is essentially goofy - in the cynical 1980s and 1990s, we just can't accept that a gamma bomb would be able to change a man's physical nature so radically, so David begins to build a foundation of how and why the Hulk is this way. He examines the Hulk's multiple personalities, and even integrates the coloring fiasco that changed the Hulk from gray (in his first appearance) to green (in his subsequent appearances). These problems culminate in several blockbuster issues, including #372 and #377, when we get a fully integrated green Hulk who is intelligent and even urbane. David never stops trying to get to the bottom of who the Hulk actually is - Bruce Banner disappears for long stretches during this run, as David points us to the conclusion that "Banner" is just a façade and the intelligent green Hulk is the true personality. Just when we accept that, David again pulls the rug out from under us and makes us once again question what the Hulk actually is. Finally, in issue #425, another integration develops, and we are again thrown into confusion, as Banner is the raging maniac while the Hulk remains lucid.

He understands that this character is essentially goofy - in the cynical 1980s and 1990s, we just can't accept that a gamma bomb would be able to change a man's physical nature so radically, so David begins to build a foundation of how and why the Hulk is this way. He examines the Hulk's multiple personalities, and even integrates the coloring fiasco that changed the Hulk from gray (in his first appearance) to green (in his subsequent appearances). These problems culminate in several blockbuster issues, including #372 and #377, when we get a fully integrated green Hulk who is intelligent and even urbane. David never stops trying to get to the bottom of who the Hulk actually is - Bruce Banner disappears for long stretches during this run, as David points us to the conclusion that "Banner" is just a façade and the intelligent green Hulk is the true personality. Just when we accept that, David again pulls the rug out from under us and makes us once again question what the Hulk actually is. Finally, in issue #425, another integration develops, and we are again thrown into confusion, as Banner is the raging maniac while the Hulk remains lucid. David wrote the book for another forty (!) issues, and he probably would have kept on if policy at Marvel hadn't pissed him off, but although the issues after #425 are decent, he had lost a bit of the direction that he had managed to keep for the previous 75 issues or so. The art became sloppy until Adam Kubert came on board late in the run, even though the artists (including Liam Sharp, Mike Deodato, and Angel Medina) have done decent work on other books. Throughout his run on the Hulk, David had a succession of good artists at the top of their game - Jeff Purves, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank - who helped bring his vision to life. David's work, it seemed, became sloppier when the art did, and the succession of crossovers Marvel was indulging in during the mid-1990s didn't help.

David wrote the book for another forty (!) issues, and he probably would have kept on if policy at Marvel hadn't pissed him off, but although the issues after #425 are decent, he had lost a bit of the direction that he had managed to keep for the previous 75 issues or so. The art became sloppy until Adam Kubert came on board late in the run, even though the artists (including Liam Sharp, Mike Deodato, and Angel Medina) have done decent work on other books. Throughout his run on the Hulk, David had a succession of good artists at the top of their game - Jeff Purves, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank - who helped bring his vision to life. David's work, it seemed, became sloppier when the art did, and the succession of crossovers Marvel was indulging in during the mid-1990s didn't help. What was next for David? He is principally known for his work on the Incredible Hulk, unless people know him for his Star Trek comics. He wrote Aquaman and X-Factor during the time he was writing the Hulk, and since his work on that ended, he has done a lot of other stuff. Right now he's working on Fallen Angel, which might be a masterpiece when it's all said and done, plus various other stuff. With the exception of Fallen Angel, however, which is only 24 issues in, he hasn't done anything that has approached not only his longevity on the Hulk but its sheer inventiveness. He still has a lot of comic book work left in him, though.

What was next for David? He is principally known for his work on the Incredible Hulk, unless people know him for his Star Trek comics. He wrote Aquaman and X-Factor during the time he was writing the Hulk, and since his work on that ended, he has done a lot of other stuff. Right now he's working on Fallen Angel, which might be a masterpiece when it's all said and done, plus various other stuff. With the exception of Fallen Angel, however, which is only 24 issues in, he hasn't done anything that has approached not only his longevity on the Hulk but its sheer inventiveness. He still has a lot of comic book work left in him, though.As far as quasi-masterpieces, these three are good examples. As I have said many times, my knowledge of comics prior to 1988 is somewhat limited (many people would say my knowledge since 1988 is limited, too), so I know I'm missing several. I would count Walt Simonson on the Mighty Thor (#337-382, roughly), but I only own up to issue #355 and don't want to consider it without having read it. Does Byrne's Fantastic Four count? Didn't Gruenwald write a ton of Captain America comics, and aren't they considered brilliant? Is Michelinie's run on Iron Man a masterpiece? What about Wolfman and Perez on Teen Titans? I'm just wondering.

Anyway, thoughts on this are welcome, as usual. It's very interesting to consider when creators hit their peak and what they do after it.

Next time: the rise of the auteurs!

36 Comments:

Paul Levitz and Keith Giffen on "Legion of Super-Heroes" (volume 2), issues 287-306 (5/82-12/83). Both were at the top of their game. The two shared plotting credits, with Levitz as scripter and Giffen as penciller. They made the future look futuristic, not silly sci-fi. With Larry Mahlstedt on inks, the artwork was dynamic, crisp, clean, and you could tell who was who even with no costumes. With issue 307, Giffen started channeling Argentinian artist Jose Munoz, and his art style changed dramatically. Still, he stayed on through issue 313 (when the title changed to LSH volume 3 #1) and for the first five issues of the third series, in 12/84. Any Legion fan will point to this time as one of their favorites. Levitz continued as writer through August 1989 with some great pencillers (including Steve Lightle and Greg LaRocque) but none of them added the same spark to the plot as Giffen did in his time.

Other suggestions: Warlord by Mike Grell (50 issues all written and pencilled by him but frequently ruined with Vince Colletta inks); the first couple dozen Wolfman/Perez New Teen Titans; and James Robinson's Starman (75+ issues)

I've got to add perhaps my favorite run of a comic ever:

Joe Kelly's run on Deadpool. It was a coherent arc that developed characters, had a developing mystery that you could solve as the story progressed, and spanned 3 years.

It also didn't hurt that it had some great artists: Ed McGuinness, Scott McDaniel (pre-Batman), Pete Woods, and more.

It is the series that defined Deadpool and his motivations, showing that he could defend free will better than Captain America, at least once.

Mark Waid and Kingdom Come?

Surely his magnum opus,

so far anyway.

It was WALTER McDaniel who drew Deadpool, not Scott McDaniel.

And I didn't like Walter McDaniels' art much. The other artists were quite good, though! Pete Woods wasn't as good as he is NOW, but he was still quite good.

Been reading through Michelinie/Layton's run on Iron Man at the moment, and it probably is both their masterpiece and the definitive take on the character. There's weaknesses sure (after all the issues of alcoholic build up, the recovery is resolved in a short montage), but I don't think either the creative force behind it or the character itself have been better.

As far as David's Hulk goes, while the emergance of the fused persona was definitely a high point and something that he was building towards, I kind feel that many of the issues afterward just weren't nearly as strong. I lost interest around 400 or so and came back during the Heroes Reborn/World Without Heroes era which I personally felt were stronger reads at the time, especially the Kubert issues.

While Lee and Kirby's Fantastic Four run gets alot of attention due to how long they stayed on it, I'm not quite sure it was either creator's "personal" work of that era (save for maybe the Galactus story). Stan Lee seems to count Silver Surfer as his most personal work. And I tend to think Kirby's work on Thor was the strongest of his pre-4th world stuff because it largely served as the genesis for it (being that it delt with mythology and all, which he seemed to love).

Though I suppose you could argue that there are cases where a creator's most personally loved work isn't always his strongest material. For example, Firestorm was clearly Gerry Conway's pet project (having created the character and really pushing for him to catch on) but I doubt anyone (even someone like me who loved the title) would say it's better than his Amazing Spider-Man run.

What about Busiek on Avengers and Ennis on Punisher, both are classic runs in mainstream company owned superhero comic books.

What about Groo the Wanderer by Evanier and Aragones?

Another good Byrne/Claremont comic was Marvel Team-Up. They did a great job working the continuity of Spider-Man and his partner-of-the-month around the other titles the characters were in. Claremont wrote Spider-Man very well, and got to add dimension and humanity to the other halves of the team-up each month.

I would say that Mark Gruenwald's run on Cap was one of the best. He tore Cap down and built him up again, really defining who Cap is in the process. His run had some rocky spots, definitely, but I would say the "Cap No More" saga is his best. We got to see an interesting new character in John Walker, learning what it is to be Captain America as he tries to fill the role. You had all of Cap's former sidekicks looking for him, and becoming a short-lived team that was really cool. Their travels (With Steve Rogers as The Captain, in a rockin' new black outfit) as the others tried to convince Cap he needed to fight the government for his Captain America identity, with him seeking to redefine himself and in the meantime leading the group into all sorts of fights, were fun to read about.

Gruenwald also mined real-world political groups, concepts, and attitudes for villain ideas, creating such memorable foes as Flag-Smasher and Ultimatum, the Serpent Society, the Watchdogs, the Resistants, and Blistik. He had Cap falling for the villain-trying-to-make-good Diamondback. He also brought the Red Skull back in a convincing fashion, and brought us Crossbones, another classic Cap villain.

I'll get to Robinson's Starman next time. Trust me!

I haven't read Busiek on Avengers or Ennis on Punisher, but I think it's pretty clear that neither one is their masterpiece. Busiek's Astro City is obviously not only his best work but the one he most closely identifies with, while Ennis ... well, I'm debating over whether it's Preacher or Hitman.

Very interesting thoughts. This is why I need to dig through long boxes at conventions more often and pick up '70s and '80s comic books. Those darned kids, keeping me busy!

Pretty much every project that Alan Moore has worked on would qualify.. certainly Swamp Thing and Promethea read as very personal works.

Not a big fan of Gruenwald's run on Captain America, though there's no question that he loved the character and loved writing him. I just didn't love reading it.

Miller's run on Daredevil, clearly.

Grant Morrison's Doom Patrol, definitely.

Grant Morrison's Animal Man.

And that one fellow who wrote Sandman, the really obscure British fellow.

Didn't Gruenwald write a ton of Captain America comics, and aren't they considered brilliant?

A ton, yes; brilliant, no.

Greg, while I love your idea of highlighting “runs” of comics—always a fun thing to do, and you’ve pulled out some great ones—I must respectfully disagree with your attempt to define “magnum opus.”

You write that “[t]he idea of a magnum opus in comics is a relatively new one, I would think,” but I think there is much to disagree with here. In the very earliest days of comics and comic strips there were already acknowledged masters—those who folks in the industry were already swiping. The work of McKay on Little Nemo, Hal Foster on Prince Valiant—the list goes on and on. These were acknowledged masters in their field and widely known.

At the point the comics fandom got really going, in the late 60’s and throughout the 70’s, comics greats were already being “codified.” This is seen especially by the publication in 1965 by Jules Feiffer of “The Great Comic Book Heroes,” which reintroduced for a new generation the so-called “Golden Age” greats—the Spirit by Will Eisner, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man, Marty Nodell’s Green Lantern, and so on.

Aside from the historical angle, I must disagree on what I see your definition of “magnum opus” as. You seem to indicate that it is the conscious writing of a masterpiece, or when an artist puts pen to paper with the awareness that there are attempting to create what is their best work.

However, you seem to immediately confuse what I think is your definition of magnum opus by referencing Shakespeare. Even at the height of his powers, the Bard was like our own Chris Claremont—maybe he was writing as lofty as possible, but he always splashed in some stuff for the folks down front. Hamlet is considered a masterpiece by us, and likely was not an attempt by the man himself to create one. It was just “work for hire.”

I also think the comics you reference as examples of magnum opera don’t fit your definition. Did Claremont and Byrne set out to create their absolute personal best? Maybe, but it was still strictly within a relatively repressive artistic world (a/k/a Marvel). The same think with the Moon Knight run: still very much comics created in a strict corporate environment with an eye towards sales.

The definition of “magnum opus” is more strictly what we perceive as the artist’s actual best work--not what they think is the best work. I think your definition is very interesting, but I would submit that the comics you have analyzed are actually what we’re perceiving as the artist’s best work. Sadly, it seemed that when the creator-owned properties really took off, what the creators thought was their best work—or the work they chose to put out there—was nowhere near the quality of their work-for-hire (John Byrne’s “Next Men;” George Perez’ “Sachs and Violens;” Peter David’s “Spyboy”). There are notable exceptions to this (Mike Mignola’s “Hellboy”) and examples where the creator was able to flex muscles that wouldn’t have been used in a more corporate environment (Frank Miller’s “Sin City,” “300”).

This is a fantastically written entry and has given me much food for thought. I certainly agree with you that it is possibly easier for an artist to now put pen to paper on their persoanl attempts to create art, but it may be just as easy to find greatness in odd and corporate places (Ladronn on “Cable” has always been my biggest surprise!). Maybe the real question is—has the rise of creator-owned properties actually allowed artists to produce better work? Or has it led (as some have speculated vis-a-vis Image) to lazier and more self-indulgent work?

Oh MY, I didn't realize that was so frickin' long . . . I have to agree with the Starman nomination by Michael and Greg, also the LoSH nom and shout-outs for Doom Patrol and Animal Man, and jr's assessment of Firestorm.

Also--the Michelenie/Frenz/Palmer run on Star Wars rocks (seriously!), Darywn Cooke's The New Frontier, Gilbert Hernandez' Palomar stories, and Jaimie Hernandez' Locas stories.

gorjus - I certaintly agree with you that in terms of history, there's definitely older stuff. I would put Tintin and Asterix and Obelix in an exalted place. I haven't read much of the older stuff, but those two titles are very good.

As for you disagreeing with me, you're right, and that's why this is a two-part post! I would disagree with your assessment of Hamlet, however, because although Shakespeare was writing for the crowds, by the time he wrote Hamlet, I'm pretty sure (I could be wrong) that he was doing well enough that he didn't necessarily have to pander to the crowd in every play. His later work is definitely an attempt to create more high-brow stuff, and that's what I want to consider.

Of course when a writer (or artist) sits down to create a masterpiece, especially as it's their own work, there's no guarantee of success, and occasionally it will be worse than their corporate stuff. That's why I think the Hulk is David's masterwork rather than some of his creator-owned stuff.

It's something I will consider in my next post, because these ones here are by necessity limited. Once we get to Moore and Gaiman and Ennis and Robinson on Starman and Wagner on Grendel (all of whom I will consider next time) we can look more closely at whether or not a creator-owned work is a better thing to work on than a corporate character. Editors can be helpful, after all.

Regarding Sienkiewicz, I tend to think that his New Mutants run with Chris Claremont is his masterwork.

Re David on Hulk: I would include "Ground Zero" (despite early McFarlane art I've never liked) and "Future Imperfect" (my favorite Perez comic) with the issues you cited. Thank you for reprinting the best Hulk cover ever (372) for those who have never seen it.

My favorite Sienkiewicz artwork: Voodoo Child: the Illustrated Legend of Jimi Hendrix. Still, I think either Stray Toasters or Elektra Assassin is his magnum opus.

I don't know if the definition of magnum opus fits, but I'd include:

Barry Windsor-Smith's Storyteller (tragically short-lived), Alan Davis' Excalibur, Sam Kieth's Maxx, Ostrander & Mandrake's Spectre, Grell's Jon Sable, Ennis & Dillon's Preacher, Gerber & (mostly) Colan's Howard the Duck, and Wolfman & Colan's Tomb of Dracula.

No to Wolfman & Perez' Teen Titans; it's not nearly as good as it's reputed to be.

i think the only bit of this I'd question, as gorjus said, is the whole "sitting down to create a masterpiece" business. but that's to me a negligible point--writers and artists don't determine their masterpieces; readers/critics/time/history do.

this is such a great write up, by the way.

i'd also like to open the discussion beyond giving any particular artist and/or writer just ONE masterpiece. i think you could probably make cases for different runs on different titles by some particularly amazing writers as all being great work.

hell, this could just devolve into a consideration of kick-ass runs without the more evolved consideration of "masterpiece" and i'd be happy. my want list is already getting a workout.

a few nominations I'll toss into the ring:

Gruenwald on Quasar: I really loved this book, especially his Operation Galactic Storm story. I just thought it was so neat. then again, I was like thirteen. I do think this would seem to be more of a personal project for Gruenwald than Cap, but I could be very wrong on that.

Grant/Breyfogle on Detective Comics: The era right after issue 600 but before Knightfall bullshit. Consistently strong storytelling with one of the most underrated and evocative depictions of Batman maybe ever.

Busiek/Perez on Avengers: I second this nomination. Lately I've just been thinking at random moments of that page in their Avengers 1 when thor bursts thru the windows--what a fucking cool moment that was. Genius.

My set of nominations: Ostrander's Suicide Squad run. Cases can be made for the whole thing or stopping at #50.

Giffen's League run up through JL:A#45.

And Cerebus between the start of High Society (or, arguably, the Palnu Trilogy) and the end ofJaka's Story.

"It was WALTER McDaniel who drew Deadpool, not Scott McDaniel."

Gah...it's been too long sine I read those...I just remembered a McDaniel in there somewhere. And yes, not his greatest work, but he did al alright job somewhat imitating McGuinness.

I also have to second Sandman...I don't even think of it as a comic anymore, as I have a Neil Gaiman shelf where tons of stuff resides in a separate place from my comics. Kudos to whoever suggested that.

I absolutely have to agree with Joe Kelly's Deadpool run, 1-33 + a couple specials. A perfect blend: humor and drama, longer character building arcs and entertaining single issues, Blind Al and Morty... one of my all-time favorites.

Other high-ranking "quasi-masterpieces" (using the definition of company-owned characters):

New Warriors by Fabian Nicieza, Mark Bagley and Darick Robertson. After Nicieza left, the book may as well ended, but while it was there, a great coming-of-age book.

Power Man & Iron Fist by Jim Owsley and Doc Bright. These men revitalized the series, adding a sense of fun while turning the title duo's lives tragic.

(This team's "Quantum & Woody" is amazing too, but belongs more to the "auteur" group)

Justice League International by Giffen/DeMatteis/Maguire. Few teams have worked together as seemlessly as these three. Their work is timeless and instantly recognizable. They reinvented the idea of superhero team and - from about issues 1-mid 40's + specials - did a "funny" comic better than anyone.

Four amazing creative teams. And JLI is the only one of this batch that's been reprinted/collected at all (and even there it's only the first 7 issues). Sigh. That's just depressing.

Some good ones here, but looks like you may have forgotten:

G.I. Joe #1-50: Larry Hama took a licensed toy comic and gave it a complex, rich backstory far beyond what anyone expected. Hama took the sketches he came up with for Hasbro (he created the characters for the toy line) and expanded ad nauseum. The characterization is great, the stories suspenseful, the arcs influential. Slipped a lot later on, but those 1st five years are golden. A war comic soap.

Byrne's Fantastic Four: So, so good. For me the definitive run on the book. Yes, more than Lee/Kirby, because it was the first book I saw to really build on a coherent universe mythology. You really felt the FF were Marvel's iconic superteam. Also Byrne at his drawing peak. Byrne defined most of what we now think of as classic Dr. Doom. To this day if The Thing doesn't look like Byrne's, he looks wrong to me.

Grant Morrison's Doom Patrol: Mentioned earlier, but let it be said you would never have anything like the Authority or Planetary without this bizarre, creative mayhem. The ending to the story is incredibly powerful- do NOT read spoilers ahead of time. Issue 57 is also one of the craziest retcons ever, at a time when almost no one did that. You must not read spoilers! It's so worth it.

Frank Miller's Daredevil: So obvious , but not at the time of the original run- remember, DD was always a 2nd rate hero with lame villains. Now he's the genesis for the more realistic Milleresque Batman everyone expects.

Roy Thomas on All Star Squadron: What happens when you give a superfan a whole world to play with (Earth-2)? A comic where you already know they good guys 'win' but where anything can happen. A cast so large it makes the LSH blush. Pure fun.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons on Green Lantern Corps: 2000 AD style British space fantasy ported directly over to a Silver Age clunker, from the Watchmen team.

Wasteland (late 80's): A comic no one read, dreamed up by improv master Del Close and anthology contributions from an all-star cast. Likely in a quarter bin near you. It's Twilight Zone for comics fans.

Mark Waid's Flash: The kind of straightforward cape adventure that is rarely done anymore. Had real, life-altering changes mixed in with light action-adventure. Completely redefined Wally West from whiny sidekick in boots too big (see Kid Flash in any New Teen Titans) to a Man in Full inheriting a legend and improving on it. A huge, multiyear run.

While I definitely think "Phoenix/Dark Phoenix" was Claremont's opus, I hesitate to exclude the rest of his run, mainly because I consider Jean's story an extension of Scott's, which in turn forms around the larger Xavier saga of the first half of Claremont's run, and then the Magneto saga of the second half. Of course, it's easier to take Phoenix on its own merits, but I think Claremont's stories in particular among comic writers are intentionally designed to never have an "okay, that story's done" finality that an opus requires.

Over at the Longbox, someone brought up Claremont's Jaspers' Warp, which I think could have supplanted Phoenix as his opus had Alan Moore not kiboshed it. At the time, Claremont was still going strong with the Lifedeaths, the Wolvie/Deathstrike story, and his work on the New Mutants. Unfortunately, the Warp story became basically illegal around #206, so the Massacre was rewritten with Sinister and the Marauders instead of Jaspers and the Fury. Personally, I think much of the sucktitude of the mid-200s comes from Claremont trying to incoroporate as much of the dead plot as possible into situations that didn't fit. So rather than a streamlined, if still immense, arc of Mad Jim Jaspers starting the Days of Future Past, we get increasing convolution in what became Sinister's Mutant Massacre/Inferno, the Adversary's Fall of the Mutants, and the Shadow King's Muir Island Saga.

As for other opuses, I'll chime in with Alan Moore's From Hell, Gaiman's Sandman, Ennis's Preacher, Waid's Flash, Ostrander's Spectre, Bendis's Daredevil (yes, over Powers, which doesn't have as much an overarc), Robinson's JSA work (including Starman and The Golden Age, Elseworlds be damned), Wagner/Seagle's Sandman Mystery Theatre, and Simonson's Thor. As for Morrison, I shift between JLA, The Filth, and The Invisibles, mainly because Morrison sort of defies the opus mentality. Maybe DC One Million?

Damn. Grant, Wagner, and Breyfogle on Detective. Slipped my mind. Which is weird, because I just re-read those and wrote a Comics You Should Own column on them which will appear some day. It's definitely Breyfogle's masterpiece, simply because he hasn't really done anything else, but I wasn't sure about Grant and Wagner, since they also did Judge Dredd (right?) and I haven't read those.

Those Hama G.I. Joes also have Golden on art for some of them, if I'm not mistaken. Those are issues I have always meant to buy. Someday ...

I'll get to Doom Patrol and Frank Miller. Fret not!

And cove west - yeah, that was me bringing up John Jaspers over at Dave's Long Box. That would have been so cool if Claremont had been allowed to do it I think my head would still be exploded.

There was a period, from around 368 to 400 or so, where Peter David's Hulk was just about the only comic book I bought every month without "previewing" at the store. The quality was so high I didn't worry that I would be disappointed. I have to agree with JR, though, that after 400 my interest waned slowly until I dropped the book entirely sometime around the issue where Banner and Rhino face off in a baseball game (it was fun, but even there Peter David was repeating himself, as he had done a similar story with those two a few years earlier).

There were dozens of reasons why that era was so terrific - Dale Keown's art, humerous subplots like Rick Jones writing an autobiography, the Pantheon as a convenient explanation for everything (now, Hulk is picking battles instead of coveniently running into villains on the road somewhere, and the Pantheon's vast wealth explains where Banner's getting the money to survive).

But the two best elements of David's run was the psychological background he created for Hulk/Banner (as has been discussed already), and the redefinition of Banner's relationship with Betty Ross, which took quite a few turns into new territory. One of the strongest images I remember came in one issue just after Doc Samson "integrated" Banner's personalities into the intelligent green hulk. Banner meets Betty for the first time in his new form, and she's clearly afraid of him. Banner turns away in anger. I'll never forget it. (and even in this scene, David's terrific sense of humor was still intact - when he storms off, Banner smashes a car on the street into a heap. Rick Jones runs to catch up, and having not seen the damage Banner inflicted, wonders who would bother to own such a piece of junk).

How about John Wagner on Judge Dredd?

He's been writing most of the tales for the past 29 years and still keeps them to a high standard and is always evolving the character.

Block Mania/Apocalypse War still stands as a high point in the characters history, and many of the big names in comics have totally failed to hit the right note with the character.