Comic Books And The Radiant, Heavenly City

In Promethea #1, her heretic father comes afoul of a Christian mob set to kill him. Rather than let them dictate the situation, he decides to instead control his own death, even writing their words as they kill him.

His last words, which he left to be the dialogue of his murderers, were, "There, time claims him. Time, and the radiant, heavenly city.”

The scene that directly follows Promethea’s father’s declaration of the heavenly, radiant city is another type of city - the New York City of 1999, as seen through the world of Promethea and the mind and eyes of Alan Moore and J.H. Williams III.

Their New York City is a gritty, yet futuristic version of the actual city. This New York City is not what New York City actually is, but rather, what New York City feels like. It is a land where even the most fantastic elements of the city, like the radical signs in the majestic skyline, are used to advertise something sordid, like pornography.

The city, as it does in the hard-boiled detective novels that helped make up the pulp fiction market (of which Moore has spoken that ABC was partially his attempt at recreating), is just as much a character as anyone else in the story. It also affects the story itself as both a reader and writer.

The city is written by the people who make up its population, while at the same time, it writes them in the way that people who enter the city are drawn into its mannerisms and its rituals. If its people change the city, it changes the people who come into it as well.

This effect exists not just in the pages of Promethea, but in many other comics.

Some examples of this relationship:

Stan Lee made a point to set heroes like Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four in New York City, rather than a fictional city. The effect of this was to ground the characters in reality, and presumably make them more accessible. Over the years, however, this "grounding" has not occured as much, I do not believe, as the "New York City" in most Marvel comics is no different from Metropolis, for all the authenticity it has as being New York. Some notable exceptions to this were a series of Daredevil writers (Frank Miller, Ann Nocenti, DG Chichester and Brian Michael Bendis all have done a good job of grounding Daredevil inside New York City, and allowing New York City to become a major character in the stories). I have yet to see the equivalent in a Spider-Man series (besides some occasional nods to New York City by various writers).

Frank Miller certainly embraced the idea of "city as character" in his series of Sin City comics, where the only thing that stays consistent in the comics IS the city itself.

Along the same lines as Miller, in James Robinson's Starman, the city of Opal is as important of a character as anyone else in the book. The history and mystique of the city is central to many of the characters whose stories are intertwined in Robinson's narrative, and Tony Harris' distinct vision of the city weighs heavily on the way in which we take in the characters.

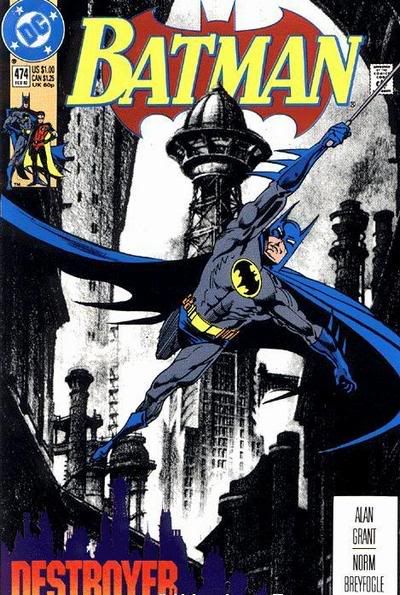

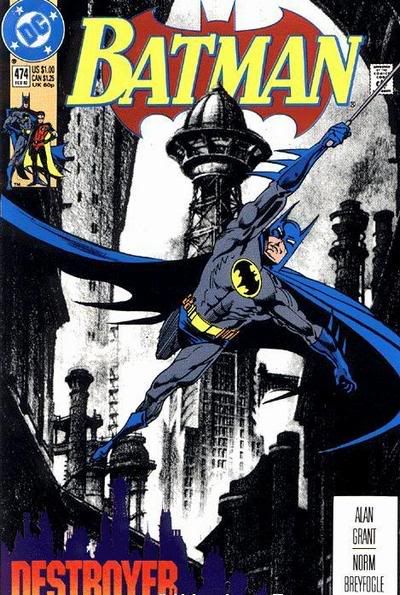

The effect Gotham City has upon Batman was dealt with in an interesting arc back in 1992, where the Production Designer of Batman, Anton Furst, redesigned Gotham City for the comics, and the storyline, titled "Destroyer," dealt with the effect that the very look of Gotham has upon influencing the ATTITUDE of Gotham.

This idea of a city influencing the very attitude of a comic, that was evident in Robinson's Starman and alluded to often in Batman comics was made clearer in some other recent DC titles, specifically Chuck Dixon's Nightwing (Bludhaven), Geoff Johns' Flash (Keystone City) and Johns' Hawkamn (St. Roch).

However, in all three instances, after the initial work that was done with the integration of the cities, I think they all also devolved into "genericville," which never happened with James Robinson's Opal City.

Fantastic Four: Big Town, by Steve Englehart and Mike McKone, dealt with another reality of the comic book environment. In the world of comic books, fantastic devices are being introduced every other month. It is unrealistic to suppose that none of these incredible inventions ever trickled down to the common populace, and that is what Fantastic Four: Big Town is about. It shows how New York City deals with the instant infusion of new technology it gained from the inventions by all the brilliant comic book scientists, and the way that the city adapts.

This is similar to what happened in the Superman titles in 2000, when a villain transformed Metropolis, "The City of Tomorrow," into an ACTUAL City of Tommorrow, filled with futuristic gadgets. Chuck Austen later, notably, dealt with the effects of such a transformation (in much the same way that Big Town did) in a year-long mini-series, Superman: Metropolis, where he shows how added technology does not neccessarily equal an improvement in the quality of life.

These approaches are both very similar to the depiction of Moore and Williams’ New York City in Promethea, where the futuristic advances do not seem to have really aided anyone's life to any great extent.

The first issue of Promethea begins and ends with the radiant, heavenly city (it is the title of the first issue, and it is the last phrase spoken in the issue), which shows, I believe, a certain devotion to the importance of the city that works as an almost route marker in this entire discussion.

Those writers who are committed to the idea of the city in the story (like Moore) are those who are willing to take that extra step to add the extra layer of depth to the comic. Such an effort is generally a sign that these are better writers period. The better writers will strive for meaning than blank backgrounds. The ones who are willing to settle for generic cities will also often be the ones that will settle for generic stories period.

It is these that are the cities, and stories...and WRITERS, that truly will be "claimed by time."

And we are all the better for time claiming them.

His last words, which he left to be the dialogue of his murderers, were, "There, time claims him. Time, and the radiant, heavenly city.”

The scene that directly follows Promethea’s father’s declaration of the heavenly, radiant city is another type of city - the New York City of 1999, as seen through the world of Promethea and the mind and eyes of Alan Moore and J.H. Williams III.

Their New York City is a gritty, yet futuristic version of the actual city. This New York City is not what New York City actually is, but rather, what New York City feels like. It is a land where even the most fantastic elements of the city, like the radical signs in the majestic skyline, are used to advertise something sordid, like pornography.

The city, as it does in the hard-boiled detective novels that helped make up the pulp fiction market (of which Moore has spoken that ABC was partially his attempt at recreating), is just as much a character as anyone else in the story. It also affects the story itself as both a reader and writer.

The city is written by the people who make up its population, while at the same time, it writes them in the way that people who enter the city are drawn into its mannerisms and its rituals. If its people change the city, it changes the people who come into it as well.

This effect exists not just in the pages of Promethea, but in many other comics.

Some examples of this relationship:

Stan Lee made a point to set heroes like Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four in New York City, rather than a fictional city. The effect of this was to ground the characters in reality, and presumably make them more accessible. Over the years, however, this "grounding" has not occured as much, I do not believe, as the "New York City" in most Marvel comics is no different from Metropolis, for all the authenticity it has as being New York. Some notable exceptions to this were a series of Daredevil writers (Frank Miller, Ann Nocenti, DG Chichester and Brian Michael Bendis all have done a good job of grounding Daredevil inside New York City, and allowing New York City to become a major character in the stories). I have yet to see the equivalent in a Spider-Man series (besides some occasional nods to New York City by various writers).

Frank Miller certainly embraced the idea of "city as character" in his series of Sin City comics, where the only thing that stays consistent in the comics IS the city itself.

Along the same lines as Miller, in James Robinson's Starman, the city of Opal is as important of a character as anyone else in the book. The history and mystique of the city is central to many of the characters whose stories are intertwined in Robinson's narrative, and Tony Harris' distinct vision of the city weighs heavily on the way in which we take in the characters.

The effect Gotham City has upon Batman was dealt with in an interesting arc back in 1992, where the Production Designer of Batman, Anton Furst, redesigned Gotham City for the comics, and the storyline, titled "Destroyer," dealt with the effect that the very look of Gotham has upon influencing the ATTITUDE of Gotham.

This idea of a city influencing the very attitude of a comic, that was evident in Robinson's Starman and alluded to often in Batman comics was made clearer in some other recent DC titles, specifically Chuck Dixon's Nightwing (Bludhaven), Geoff Johns' Flash (Keystone City) and Johns' Hawkamn (St. Roch).

However, in all three instances, after the initial work that was done with the integration of the cities, I think they all also devolved into "genericville," which never happened with James Robinson's Opal City.

Fantastic Four: Big Town, by Steve Englehart and Mike McKone, dealt with another reality of the comic book environment. In the world of comic books, fantastic devices are being introduced every other month. It is unrealistic to suppose that none of these incredible inventions ever trickled down to the common populace, and that is what Fantastic Four: Big Town is about. It shows how New York City deals with the instant infusion of new technology it gained from the inventions by all the brilliant comic book scientists, and the way that the city adapts.

This is similar to what happened in the Superman titles in 2000, when a villain transformed Metropolis, "The City of Tomorrow," into an ACTUAL City of Tommorrow, filled with futuristic gadgets. Chuck Austen later, notably, dealt with the effects of such a transformation (in much the same way that Big Town did) in a year-long mini-series, Superman: Metropolis, where he shows how added technology does not neccessarily equal an improvement in the quality of life.

These approaches are both very similar to the depiction of Moore and Williams’ New York City in Promethea, where the futuristic advances do not seem to have really aided anyone's life to any great extent.

The first issue of Promethea begins and ends with the radiant, heavenly city (it is the title of the first issue, and it is the last phrase spoken in the issue), which shows, I believe, a certain devotion to the importance of the city that works as an almost route marker in this entire discussion.

Those writers who are committed to the idea of the city in the story (like Moore) are those who are willing to take that extra step to add the extra layer of depth to the comic. Such an effort is generally a sign that these are better writers period. The better writers will strive for meaning than blank backgrounds. The ones who are willing to settle for generic cities will also often be the ones that will settle for generic stories period.

It is these that are the cities, and stories...and WRITERS, that truly will be "claimed by time."

And we are all the better for time claiming them.

7 Comments:

Vanity was one such town, but since Aztek only lasted ten issues, Morrison didn't get a chance to develop his vision.

A while back I read on Dorian's site that Hell's Kitchen is a thriving gay trendy tourist attraction, and that Daredevil writers are simply recycling the old cliches. I haven't been to NYC in years, but if writers actually checked out Hell's Kitchen these days, that would make an interesting comic book!

This piece missed Astro City; I mean this is a comic exactly what you are talking about, isn't it?

James Robinson's earlier series Firearm tried to incorporate the flavors of the LA area and did an okay job. Not as well as he did with Opal City in Starman, but he was constrained by reality with LA.

A series that incorporated its home city well: Mazing Man and New York. You could smell the city, by god!

DC needs to produce an All-Star Mazing Man and Denton the Dog-Faced Boy series. Now.

That's the point, Dizzy, I leave off some so you folks have something to add!

Like Vanity, which was a super cool city.

And Greg, I went to school in Hell's Kitchen only a few years ago, and sure, there are some touristy areas, but I volunteered at a children's center there...there are still some worrisome areas. Strangely enough, it is generally only, like, two avenues over from "tourist central."

Interesting dichotomy.

Hell's Kitchen is a gay trendy tourist attraction. That just makes me laugh.

Thanks for the Promethea inspired blog. Just finished the 5th book and I love it. More people should be talking about this instead of "who I want to kill because they killed somebody in a comic book I like."

They called that concept "psychetecture." It was a cool idea. It's too bad the series didn't live up to its potential-- most of the creators seem to regard it today as a failure.

I think the most urbanistic comic I've read, in which the city is the primary character, is Cities of the Fantastic by Schuiten and Peeters. As the title indicates, this whole series is about cities; it's kind of a comics equivalent of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities. The particular album I read, Fever in Urbicand, is about a city which is divided by a river between a poor side and a rich side, until a mysterious, constantly expanding cubical structure appears out of nowhere and grows to cover the whole city.

Post a Comment

<< Home